When we left Hinton Oklahoma, our plan was to make Amarillo Texas by the end of the day. The distance is only 210 miles and the drive on the interstate would only take three hours. But we were taking the original Route 66…the mileage would be a bit more and the average speed was quite a bit less. It was a beautiful Oklahoma morning, still not too hot and a clear blue sky. We dropped the top on the car and hit the road.

Ultimately, the 200 plus miles from Hinton, Oklahoma to Amarillo, Texas would take us about ten hours, but the experiences along the way would be priceless!

~~~~~

We were traveling the last part of Oklahoma on a Sunday on a long holiday weekend. We weren’t sure what would or wouldn’t be open or what kind of traffic we’d find. We just decided to make the best of it with whatever we found along the way.

West of Oklahoma City, Route 66 and I 40 run due west and pretty much parallel. Initially, the original highway is located about a half mile north of the interstate, far enough away that there’s only local traffic and no evidence of the interstate to detract from the two lane highway that runs out through the rolling hills to the horizon. This led to a very quiet Sunday morning ride.

The ride through this part of Oklahoma would take us through a mix of western Oklahoma towns and cities, none very big, many really small – Hydro, Weatherford, Clinton, Foss, Canute, Elk City, Sayre, Hext, Erick, Texola – and then the Texas border

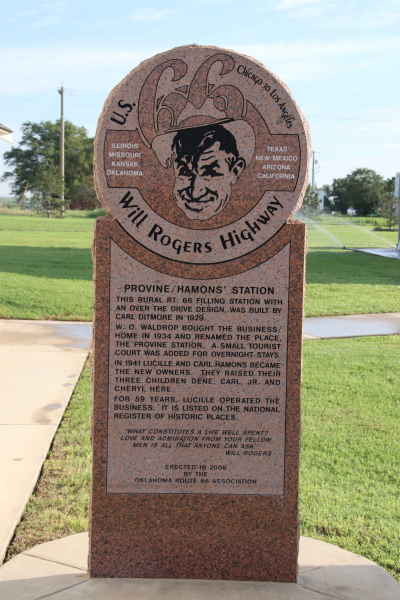

Our first stop was the restored Provine/Hammons Gas Station, situated neatly on the side of the road just west of Hext. The station is better known as Lucille’s Historic Gas Station since Lucille Hammons effectively ran the business for 59 years starting in 1941 when she and her husband bought it.

The station was built in 1929 and is characteristic of the design for rural gas stations during the era of increasing automobile travel. The small station office occupies the lower level and the living quarters for the owner/operator occupy the upper floor.

The station was built in 1929 and is characteristic of the design for rural gas stations during the era of increasing automobile travel. The small station office occupies the lower level and the living quarters for the owner/operator occupy the upper floor.

This particular station changed ownership a few times, finally becoming the property of the Hammons’ in 1941. The station was run by Lucille until her death in 2000. Lucille was known as a feisty business owner and a proponent for the Mother Road, earning her the nickname of “Mother of the Mother Road”. Even when I 40 was opened in 1971 alongside the original Route 66 and her station was relegated to a lonely location well off the nearest exit, Lucille persevered. She seized opportunity and installed a beer cooler; her best regulars were the men at Southwest Oklahoma State University in nearby Weatherford which was a dry town.

Her memory lives on at Lucille’s Roadhouse, a new establishment named in her honor in nearby Weatherford. The owners of the new roadhouse were involved in preserving the original station.

We continued our Sunday morning drive through Weatherford and into Clinton. Arriving in Clinton, we were greeted by a somewhat forsaken remnant of Route 66, the Glancy Motel.

The Glancy is a classic 1950’s chain type motel that was built next to Pop Hicks, a popular Route 66 diner since 1936. The combination of a popular diner and bright and colorful “modern” motel created a few prosperous decades for the businesses along the Mother Road. But progress and fate prevailed and between the re-routing of Route 66 to the interstate in the mid 70’s and a fire that destroyed Pop Hicks in 1999, the Glancy went into a downward spiral. After a brief flirt with restoration in the early 2000’s, the property continues to stagnate and today looks near abandoned.

We continued into Clinton along the original route and found the main downtown street closed off for a block party later in the day. Our detour one block over led us to finding a great restoration of an early 1920’s lumber store into a coffee shop and offices.

The vacant lumber yard was purchased by the Strayhouse Kitchen and Coffee in 2016 and has embarked on a journey to restore the building with attention to its prior life. The original signage, though faded and in disrepair, is still present. The two drive through bays that trisect the building and allowed lumber trucks to load under cover are now repurposed, one providing a covered dining patio, the other providing drive through access to the coffee shop and covered access to eclectic offices and shops. The old wooden storage shed in the back of the property is still present and may offer commercial opportunities to an enterprising entrepreneur. Kudos to Strayhouse for working to get this rough rock polished to a productive gem.

Initially, Clinton was of interest as the home of the Oklahoma Route 66 Museum. Unfortunately, we got into town around 10AM and, because it was Sunday, the museum wouldn’t open until 1PM. The building is a glitzy art deco retro design that is enticing and a nice informative visit (we knew this from our stop when we passed through town in 2012). It was a bit disappointing, but we needed to keep moving and, since we had been through the museum in 2012, we opted not to wait and continued on the highway out of town.

Just as we reached the outskirts of Clinton, we found one last relic of the original highway, McLain Rogers Park.

The 12 acre park was originally built between 1934 and 1937 as a cooperative WPA effort to provide employment for Clinton citizens during the depression. Though designed as a city park, with pavilions, a bandstand, and a variety of recreational opportunities, the park also enticed travelers on Route 66 with its classic art deco entrance pillars and original neon signage facing the highway.

As an additional tie-in to the Route 66 history, the small fieldstone building just to the left of the entrance to the park was the last structure built (1941) and was designed initially to house an outpost of the Oklahoma State Patrol, whose work was increasing because of increasing traffic on the highway.

As we left Clinton, we continued our cruising on the old configuration of Route 66, which pretty much followed along the frontage roads of the newer I40. Between Clinton and Canute, just east of Foss, the route had us cross over from the southern frontage road to the northern frontage road at one of the I40 underpasses. As we pulled through the underpass, we found a huge colony of cliff swallows and stopped to get some pictures as they swooped in and out of the underpass to feed their broods in their gourd shaped mud nests.

Swallows roosting under the overpasses would become a common sight as we traveled along Route 66 in the southwest. They always lived in huge groups of hundreds, maybe thousands of birds, swooping and diving against the bright blue sky. Each trip through one of these underpasses would bring to mind the movie “The Birds” as we continued down the road.

Little Canute, Oklahoma was pretty much orphaned when I40 took over the traffic from Route 66 in the early 70’s. The original Route 66 was routed as the main drag on the northern end of town, with the main street intersecting the highway at a tee. Rather than disrupt the small city with a major interstate, the super slab was curved to the north, away from the outskirts of town by a half mile. Access to Canute from the interstate is now through one exit at the east end of town and a half mile north.

Before the super slab, the Mother Road was the north end of the city and it had several traveler related businesses. What Canute offers today are the ghosts and remains of those businesses.

The first remain we saw was the oft photographed Cotton Boll Motel sign. Once a popular stopping place for travelers, it has now fallen into disrepair and is virtually abandoned, though by some accounts it still serves as a single family residence.

Next up along the highway was the Canute Service Station, listed on the Register of Historic Places in 1995. The building actually started as a dance hall and roadhouse (west end of the building not under the canopy) in 1936 and the gas station and service bays were added in 1939.

The building, especially the gas station, has a somewhat art deco pueblo architecture. The canopy would have sheltered gas pumps and there were three service bays lining the west side of the building, which fronted Main Street.

Just west and on the other side of the highway are the remains of another gas station, referred to by the locals as Kupka’s Station. Based on the style, the station is probably just a bit older than the Canute Station across the street.

The canopy has a bit of an art deco look with its curved edges. The station was also built with two service bays, reflecting the practice of providing additional services to travelers to improve revenue. Though competitors, the two stations in close proximity actually serviced two groups of travelers on the highway, with one conveniently situated for the westbound trade, the other more convenient for the eastbound.

On the west end of Canute, the old highway is anchored by another ghost of a motel sign. Standing quiet and lonely near the edge of the road stand the remains of the Washita Motel sign, once a bright neon beacon for travelers looking for a place to stay.

Besides the ghostly remains of businesses, Canute also provided an interesting configuration of the old Route 66 and how it yielded to progress of the Interstate. Just a half mile west of town, we had an opportunity to view, walk on, drive, a short (three tenths of a mile) section of original 66. This was the western remnant of the old 66 that effectively formed the northern edge of Canute.

When the interstate was built, it was routed north of Canute about three tenths of a mile, around the city. On either edge of town, the interstate right of way effectively used the right of way for the Mother Road. An arial view of the road configuration shows how the interstate effectively crossed over the original Route 66, relegating the original highway to a “frontage road” status.

Nonetheless, the original highway physically exists and provides a great opportunity to drive on the historical roadway. The grass growing between the concrete slabs tells the story of abandonment, but the narrower width of what was a two lane road and the gentle graded curb on the shoulder speaks of highway construction in the 30’s.

I stopped at the end of the road for just a bit contemplating the thoughts of the drivers in the 30’s and 40’s as they traveled west, nothing before them except this thin ribbon of concrete running to the horizon.

Leaving the ghosts of highways past behind us, we continued down the road towards Elk City, Oklahoma. As we entered the downtown area, we ran across a larger older building that advertised a relationship with Route 66 as the site of the 1931 Route 66 Conference, an organization created to advertise and publicize the highway.

As it turned out, the building is listed on the National Register and was originally built in 1928 as the Casa Grande Hotel. The Spanish Eclectic style hotel was built on Route 66 at roughly the half way point between Oklahoma City and Amarillo to provide luxury accommodations for the increasing number of travelers on the major highway.

Though it may not be much to look at today, the hotel in its day was known as a luxurious establishment, with a large two story lobby, elegantly furnished and decorated. The building is still listed as the Anadarko Basin Museum of Natural History, a privately held museum dedicated to one of the largest oil and gas reserves ever known in the US. The museum is no longer open because of funding issues. It will be interesting to see if somewhere along the line, a “guardian angel” comes along to save and perhaps resurrect the property as a boutique hotel.

The next stop in Elk City was the National Route 66 Museum, one of a number of museums at the Old Town Museum complex on the west side of the city. We had stopped at this museum six years ago when we took Route 66 to the half point and found it rather interesting and we hoped to make the stop again. Alas, Sunday hours did us in again; we got there about 11:30 and the museum wouldn’t open until 1PM. With the miles we needed to cover, we knew we couldn’t wait. Still, the outside grounds were accessible and the plantings, water garden, and recreated old buildings provided a brief respite before we hit the road again.

We weren’t the only ones who found out the museum was closed. While we meandered the grounds, we met a small group of travelers from France working to get their picture taken under the large Route 66 sign.

We also met two couples from Ohio who were making the trip on Route 66 in reverse. They had flown to California, rented a matching pair of new Ford Mustang convertibles and were working their way back to Chicago for their flight back to Dayton.

Leaving Elk City, we bobbed back and forth on the I40 frontage roads heading to Sayre. A treat along this old configuration of Route 66 was a ride across the endangered Timber Creek truss bridge.

The 96 foot Pratt through truss bridge was built in 1928 and faithfully served Route 66 as the path across Timber Creek until 1958 when the road was upgraded to a four lane highway and routed just north of the old bridge. By 1966 the four lane highway was upgraded to interstate status and the old highway became just another stretch of frontage road.

Today, people passing by on I40 just a couple hundred feet north of the old girder bridge may see it as just a quaint two lane country bridge nestled over a quiet creek (if they notice it at all!), unaware that for 30 years that sturdy girder bridge was a key part of the infrastructure that carried hundreds of cars and trucks daily on their trips east and west.

Between Sayre and Erick Oklahoma, just north of Hext, the original four lane path of Route 66 wanders north of I40 for about five miles. Though travel is restricted to the two east bound lanes – the westbound lanes are blocked with large growth trees at each end – the abandoned west bound lanes lie just north of the lanes that are used, present as a ghost of the Mother Road’s past.

The road is technically closed, but it’s still possible to get out and walk the concrete lanes, thinking about the days when this road was a major thoroughfare with heavy traffic in both directions. Today, the road is well removed from the interstate, with only the sound of the Oklahoma winds and an occasional car passing on the nearby two lane to break thoughts of days past. Though the road looks a little forlorn right now, there is some talk about the original road becoming part of a regional bike trail.

Just down the road from the historic four lane section of Route 66, we cruised into the small city of Erick Oklahoma, what would turn out to be the last significant populated area of Oklahoma. The small city is somewhat famous for being home to two of Country music’s more peculiar music legends. Sheb Wooley, the songwriter and singer who recorded the saga of the “one-eyed, one horned flying Purple People Eater” was born in Erick in 1921. In addition, the light hearted country superstar Roger Miller, most famous for “King of the Road” and “Dang Me”, grew up in Erick from the age of three.

As we drove through the sleepy town we were drawn by the eclectic exterior décor of the Sandhills Curiosity Shop on the corner of 3rd and Sheb Wooley Street.

There is no way to fully describe the appearance of the building/store except to call it “eccentrically eclectic”. Based on the “City Meat Market” ghost sign still visible over the canopy, the building had a more essential past as a butcher shop, and amongst all the signs on the outside was one that proclaimed the building the oldest brick building in Erick. But now the signs suggested any number of possibilities including antique store, junk shop, museum, or…?

As I was walking around the outside of the building taking pictures, a middle aged couple walked out of the store. The woman looked at me, smiling and shaking her head in disbelief. Without me asking anything, she said “There is no way to explain it. You have to go in and experience it yourself”.

Into the “store” we went and proceeded to meet Harley Russel, proprietor of a store that sells nothing but good feelings and entertainment. The “store” is literally filled to the ceiling and front to back with a collection of memorabilia and historical items, none of which are for sale, all of which are for looking, touching, and bringing back memories.

The beginning of the Sandhills Curiosity Shop goes back a number of decades when a young girl with a musical inclination by the name of Annabelle stopped in a small shop in Erick when she needed a string for her guitar. There she met Harley and the two quickly got together as co-owners of the shop.

Their break came one day when they jamming on their guitars when a tour group stopped. They continued with an impromptu performance that was well received and resulted in sizeable tips. The driver of the tour bus promised future visits and Harley and Annabelle, billing themselves as the “Mediocre Music Makers” became an Erick sensation and celebrities on Route 66.

The performances virtually ended in 2014 when Annabelle succumbed to cancer. Nonetheless, Harley still opens his doors to travelers on the Mother Road and he easily shares his fond memories and stories and friendly banter with anyone willing to listen. And he still enjoys entertaining.

While we were there, another couple stopped in and as we were all perusing the items he’s collected in his store, Harley picked up one of his guitars and asked if we’d be interested in hearing a song. After a very mellow intro on his guitar, he broke into a rousing performance of “Get Your Kicks On Route 66”.

It was a great visit to a great icon of the Mother Road, perhaps one of the best memories we came back with.

Just before we reached the Oklahoma state line, we drove through the small town of Texola. Though it was never “big”,Texola did reach a peak population of 581 in the 1930’s shortly after Route 66 was routed through the town. Today the town has shrunk dramatically. With a current population of 38, the town is considered a virtual ghost town, with just a few remnants of buildings from its boomtown days when the Mother Road brought in travelers and prosperity.

Slightly off the old highway is an old territorial jail, built in 1910, that was apparently a popular roadside attraction in the days of the Mother Road. Today, the sturdy but somewhat forlorn jail, now over 100 years old, stands marked with a stone monument placed by the 1938 Texola Senior Class.

The little town was a bustling farm town in the 30’s, with enough local trade to support four cotton gins. Today, those buildings are gone, save for one that survives as a private storage building.

The old main street is peppered with the remains of businesses from the old days, including an old Magnolia Service Station that made it to the National Register.

Leaving Oklahoma behind us, we continued west to take the Mother Road across Texas.