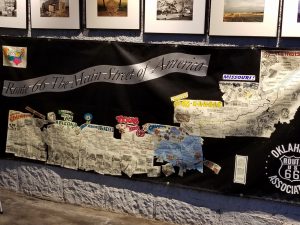

After Tulsa, Route 66 continues to the southwest for only a bit before reaching Oklahoma City, where it takes a distinct turn to the west. At the same time, the landscape starts to transition from the wooded hills of the east to the more open and flatter plains of the west. From Tulsa to Oklahoma City, the Mother Road goes through a rapid succession of smaller towns – Sapulpa, Bellvue, Bristow, Depew, Wellston, Stroud, Davenport, Chandller, Warwick, Wellston, Luther, Arcadia – before reaching the westward turning point of Oklahoma City.

As we cruised down the road, there were several places we passed that captured our attention and provided background to the historical aspects of the road.

Sapulpa and 66 Foot Gas Pump

To quote Jerry McClanahan (EZ 66 Guide for Travelers, 4th Edition), “Old 66 is full of larger than life people, animals and objects” and it doesn’t take long for anyone following his guide to get caught up in noticing the “Giant” and “Big” things on the route.

I can’t fully recall the reason, but the appearance of a giant gas pump on the horizon garnered Kathy’s interest as a photo op, something to send to her brother in answer to a challenge he issued. We kept our eyes on the sight and ended up following the road to the Heart of Route 66 Auto Museum. The iconic 66-foot-tall gas pump was built as a beacon to draw travelers to their recently opened museum just off Route 66.

Though we didn’t take time to tour the museum ourselves, it did appear to be sleek and well curated. In fact as we were pulling out to continue our drive down the road, there was a huge contingency of old, well restored cars pulling in to visit.

Just Outside Sapulpa – Three Miles of Original Route 66

We left Sapulpa on the last iteration of four lane Route 66. Just west of the city we veered to the right onto a quaint 3.3 mile stretch of old, pre-1952, Route 66.

The original 66 used an already well-developed stretch of road through this part of the state, a road that was based on the old Ozark Trail. The relatively well-developed infrastructure made it easy to incorporate the road into the new national highway

The first thing we saw pulling on to the road was the Rock Creek Bridge, a Parker through-truss bridge, built in 1921 to serve this stretch of the Ozark Trail. One of the aspects that made the bridge special was that it was constructed with a brick deck.

The bridge was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1995. Though it has a weight limit of 4T and is clearly marked for low clearance with a 7’2” height limit, it still carries traffic today down this historic bit of Route 66.

Just after the bridge, an overgrown structure on the left side of the road caught my eye. It was an early drive-in theater screen. Staked in the tall grasses alongside the road near the property was a “For Sale” sign.

Heavily overgrown, the drive in was long abandoned. Besides the screen, it was possible to make out the remains of the ticket booth and the small projection/concession stand in the open area where the cars would park.

Heavily overgrown, the drive in was long abandoned. Besides the screen, it was possible to make out the remains of the ticket booth and the small projection/concession stand in the open area where the cars would park.

A bit of on-line research showed the property to be the former TeePee Drive-In, built in 1950 on what was then Route 66. It had space for 400 cars, and it remained a business until it was abandoned in 2000. Based on comments that I found online, there are quite a few people in the area that harbor fond memories of the TeePee in its early years.

There was a failed attempt at a restoration in 2012, and now the property is up for sale again. The ad by Coldwell Banker suggests “restore drive-in to its former glory or develop something entirely new.” I could easily envision a restoration to the glory of a drive-in museum, maybe with concessions available all day, a memorabilia store, maybe special shows on in season weekends of nostalgic drive-in flicks. Here’s hoping someone comes along who can plan and market a restoration to all the visitors traveling Route 66.

Leaving the drive-in behind us, we continued down the gently winding stretch toward the point it rejoined the four lane highway. Just before we reached the end, we passed under a low and narrow railroad overpass that dated back to 1926, still in use on a branch line (the Stillwater Central) today.

Kudos to Bolin Ford in Bristow – Protecting the Past

The drive through Bristow would have been uneventful if I hadn’t researched a reference to an historic car dealership before the trip. The Bristow Motor Company began as the first car dealership in the county in 1923 and it continues as a car dealership today.

Until December 2008, Bolin Ford operated their dealership on the entire city block in the historic 1923 building as well as two other historic buildings that were built in 1925 (on the corner at the other end of the block) and 1927 (as a “filler” between the two older buildings). That fateful December a fire broke out in the 1925 building and destroyed it while causing extensive damage to the other two historic buildings.

Despite the economics of the era, Bolin Ford elected to rebuild the dealership in a 1920’s style, managing to save the 1923 and 1927 structures. Though the 1925 building on the corner which housed the entrance to the dealership has been newly constructed, it blends seamlessly into the 1920’s vintage buildings on the rest of the block.

Kudos to Bolin Ford for recognizing the historic value of their property and continuing business on Route 66. Instead of taking the easy way out just building another big box car dealership, they made a concerted effort to preserve their history.

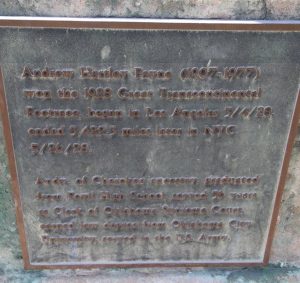

Chandler – One of the Most Interesting Museums on the Mother Road

After Bristow, we worked our way down the road to Chandler. We had one stop planned for Chandler, but we also found another gem as we went through town.

Chandler is home to artist Jerry McClanahan and his Route 66 Gallery is just off the route. Jerry is also the author of the EZ 66 Guide For Travelers, now in its 4th Edition. Jerry started traveling Route 66 with his family during the 60’s and his love for the road turned from hobby to livelihood in the 90’s.

The EZ Guide can easily be described as the bible for anyone making the pilgrimage on Route 66. We used it for our first trip on the road in 2012 and we upgraded to the latest edition for this trip. It is the best base resource for anyone making a trip on Route 66. Now that we stopped at his gallery, our latest edition is an autographed copy!

As we were driving through Chandler, we found what was probably one of the most interesting museums on Route 66 when we passed a 1937 Armory that has been restored. The Armory was built as a WPA project and it stands proudly at a wide left turn as Route 66 heads into town from the east side. The Armory was solidly built from local sandstone, the large blocks individually hewn and fitted. The building was used through 1971 when the National Guard moved to a new facility.

As we were driving through Chandler, we found what was probably one of the most interesting museums on Route 66 when we passed a 1937 Armory that has been restored. The Armory was built as a WPA project and it stands proudly at a wide left turn as Route 66 heads into town from the east side. The Armory was solidly built from local sandstone, the large blocks individually hewn and fitted. The building was used through 1971 when the National Guard moved to a new facility.

By the 90’s, the building had fallen into disrepair and there were thoughts about demolishing it. The local citizens prevailed, had it listed on the National Register and by 1998 a restoration group was organized.

The restoration was completed in 2008 and includes a civic event space with a restored section of the original drill floor.

An interesting part of the restoration involved paying homage to the Mother Road that ran past its doors with the creation of the Chandler Route 66 Interpretive Center, now housed in the restored Armory. The Center is unlike any other Route 66 museum, investing heavily on video and pictures to tell the story of the Road. There are several video stations in the center that have large TV’s set up that play videos telling bits of the Route 66 story from different eras. The seating for guests is provided by actual seats from a Model A Ford, a 1940’s vintage Willys Jeep, and the seats from a 1965 Mustang. There’s also a video station that plays videos about the classic motels and neon signs that can be found on the Route, where guests can lie back on a bed to watch the movies.

The Armory was a great stop, an interesting historical building and example of a fantastic restoration. Adding the well curated and interesting Route 66 Interpretive Center was a great idea, pulling in visitors from all over the world as they drive Route 66.

Luther – A Bit of Black Americana on the Mother Road

While researching things to see on Route 66, one of the sources I used was a site curated by the National Park Service and dedicated to preserving the heritage of Route 66 (https://www.nps.gov/Nr/travel/route66/index.html). The website included a great list of sites along the route that are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. While perusing the sites in Oklahoma, there was one in particular that stood out and called to me, the Threatt Filling Station. After reading the history of the station, I knew I would stop to take pictures and consider its past.

At just about three miles out of downtown Luther, we came up on a quiet intersection of US 66 and Countyline Road. The Threatt Filling Station stands alone at the intersection, lonely, by itself on the southwest corner.

I have to admit that there doesn’t seem to be anything special about the somewhat dilapidated structure. I’m sure most people would drive right by, not giving the building a second thought except maybe to think it’s time someone should tear it down. But the structure has an important history.

It was built in 1915 by Allen Threatt as a “house type” gas station using design elements popular during the time. The building was built using local sandstone and incorporated wide classic eaves on all four faces. It was set back just enough from the main highway to allow a couple gas pumps out front. What really sets it apart from the other historic sites along Route 66 is that Allen Threatt was African American and the Threat family homestead, on which the filling station was built, represented economic opportunity for the Threat family.

The station benefited from its location on Route 66 once the highway was commissioned, and it became a popular roadside stop for travelers through the 1950’s. It was one of the few places on Route 66 where people of color were welcome.

In all my enthusiasm to travel the Mother Road, I hadn’t really thought about how Black Americans would have been viewed during the height of the roads popularity. In fact, Blacks traveling Route 66 needed to be much more cautious and they had to stock up for their trip much more carefully because there were many stretches where they were not welcome. Safe refuges like Allen Threatt’s Filling Station were probably welcome sites for traveling Black families.

Oklahoma City – Lake Overholser Bridge

After our reflective stop in Luther, we continued down the road to Oklahoma City and westward to our stop for the night in little Hinton, Oklahoma. It was late afternoon and we still had about 90 miles to the motel. For travelers on today’s interstates, 90 miles may not seem like much but for the way we were traveling (two lane roads, side trips through small towns, city streets through Oklahoma City), the 90 miles left could easily take 2 ½ to 3 hours.

With the sun dropping in the sky, we worked our way through Oklahoma City, catching glimpses of some of the older and more interesting buildings along the route. As we reached the west side of the city, we took an older configuration of Route 66 which took us to a 1924 steel truss bridge that served the Mother Road from 1925 to 1958.

The original bridge was built in 1924 and opened to traffic in 1925 after massive 1923 floods wiped out every bridge in Oklahoma City. With a 20 foot wide roadway, the new bridge was wide for its time. The design was elegant and balanced using a combination of newer (for the era) truss construction spans, with pony truss spans at each end leading to four Parker through-truss spans over the North Canadian River flats that lead into Lake Overholser. The overall span of the bridge is 748 feet long.

As the traffic on Route 66 exploded into the late 50’s, the 1925 bridge was getting stressed and the highway route was relocated to a new four lane just north of the existing bridge. The older span remained open to local traffic, but was closed to traffic in 2008 because of deterioration. The historical significance of the bridge was recognized and Oklahoma City invested $4 million dollars to refurbish the bridge, which reopened to traffic in 2011.

Today, the historic bridge is the centerpiece of the northern gateway to the recreational area surrounding Lake Overholser.

With this last serene stop under our belt, we headed west into the setting sun and our last night in Oklahoma, a small hotel in Hinton. From there, it would be about 100 miles to Texas and on to Amarillo.

The hole in the wall Conoco Filling Station (as it’s known), was reportedly built in 1929/1930 on the west wall of the last commercial building on Commerce Street, squeezing in a gas station in the narrow piece of land between the building and the highway. Today, the small station is a souvenir/gift shop and museum for Route 66 memorabilia, and maintains a quaint symbiotic relationship with the Dairy King across the street. It probably was a bit more competitive when both businesses were gas stations in the 30’s and 40’s, competing for the passing traffic.

The hole in the wall Conoco Filling Station (as it’s known), was reportedly built in 1929/1930 on the west wall of the last commercial building on Commerce Street, squeezing in a gas station in the narrow piece of land between the building and the highway. Today, the small station is a souvenir/gift shop and museum for Route 66 memorabilia, and maintains a quaint symbiotic relationship with the Dairy King across the street. It probably was a bit more competitive when both businesses were gas stations in the 30’s and 40’s, competing for the passing traffic.